These days, in particular, I am often asked whether radio was actually that much better “back in the day.” The question is understandable. The scaling down of radio, the impacts of consolidation, and shrinking staffs have all contributed to a very different radio industry today than it was decades ago.

These days, in particular, I am often asked whether radio was actually that much better “back in the day.” The question is understandable. The scaling down of radio, the impacts of consolidation, and shrinking staffs have all contributed to a very different radio industry today than it was decades ago.

Like Olympic figure skating, the judging is highly subjective. What sounds good to one set of ears may be perceived much differently by others. And depending on when you first started listening to radio ostensibly as a kid (and that assumes you’re old enough to have grown up with radio), your yardstick for quality and entertainment value may be much different than others.

At the station level, a key element in coaching talent is the fine art of “getting on the same page.” Traditionally, it’s been the program director who makes that call, deciding on the format specifics, and what is “good radio” – the standard by which the airstaff is judged. While it’s true the ratings provide a measure of numerical performance, good programmers know that good or bad ratings can occur for reasons that go well beyond who’s on the air during any given time of day. They can hear when a host is sounding great (or not), and whether that explains why the ratings just went up – or down.

The other day, Gene “Bean” Baxter posted an aircheck of the legendary KHJ in Los Angeles from 1974. During it’s heyday, RKO-owned KHJ was one of the iconic Top 40 radio stations in the country. In fact, Quentin Tarantino extensively used old KHJ airchecks in creating his brilliant, throwback film, “Once Upon A Time in Hollywood,” starring Brad Pitt, Matt Damon, and others. While the 2019 film is steeped in nostalgia – cars, clothes, and jargon – it’s the KHJ soundtrack that provides the authentic atmosphere and vibe of L.A. in the 1960’s. Most movies use individual songs or artists to distinguish themselves, but Tarantino instead turned to Southern California’s most popular radio station to make his statement.

In setting up his post, Bean lays out the challenge:

“I’m not saying both music and radio were better in 1974 but you might, after listening to this.” Touché!

Like those sports/radio “debates” about whether players of different eras—like Jordan or LeBron—were better or who would win if they went one-on-one against each other, Bean’s question is more hypothetical than real. But it not only begs the question of whether radio (and/or music) was, in fact, better back in those days, but also whether the systems that permeated and defined station operations in the ’70s didn’t also lead to the creation of “better radio.”

Yes, that likely meant regular airchecking of talent—even Charlie Van Dyke, the Real Don Steele, Robert W. Morgan, Charlie Tuna, and the other “legends” who graced the KHJ airwaves during that seminal period in AM Top 40 radio. Listen to the aircheck and decide for yourself.

In the meantime, a website called “Radio Retrofit” hosted by Jon Nelson has done something fascinating in the aircheck genre. It’s a deep dive into every episode of every Dr. Johnny Fever (Howard Hesseman) break from the television sitcom, WKRP in Cincinnati. Nelson meticulously knitted together a three-hour Dr. Johnny Fever “show,” including (mostly) music the TV DJ chose.

The first break comes at about 4:15, but if you give the aircheck a few minutes, you’ll get a pretty good feel for his style and why he was a standout talent on WKRP—and a beloved character on the show. Whether PD Andy Travis (Gary Sandy) ever airchecked Fever is perhaps something we may never know.

You can access Johnny Fever’s recreated aircheck here. And by the way, it is not scoped so with the music, it runs about three-hours long.

Nelson, who hosts a show on community radio station, KBOO in Portland, OR, has recreated “airchecks” for other fictional and/or cinematic DJs, including Johnny Fever’s coworker, Venus Flytrap, along with the amazingly talented Adrian Cronauer (Robin Williams) from Good Morning, Vietnam (1987) as well as Hard Harry, played by Christian Slater in Pump Up The Volume (1990).

No one exactly knows when the tradition of programmers airchecking talent began, but you’d have to think it dates back to the very beginnings of radio when personalities were hired to do radio shows. Remember that the technology that enabled audio to be recorded actually predates the breakthrough when audio was first broadcast. Chances are, airchecks have been with us since the beginning of radio shows.

From both the P.D. and talent’s vantage point, the aircheck isn’t always a favorite aspect of the job. Because of the aforementioned subjectivity related to whether a break was funny, rambling, concise, incoherent, or good, these sessions can be contentious and even antagonistic depending on the dynamic between a host and the station’s programmer.

But the reality is the aircheck also provides the P.D. the opportunity to “check in” with talent, assess their mood and state of mind, and identify problems or misunderstandings. Sometimes the only point of contact a programmer has with talent is the time he or she spends reviewing an aircheck.

Yet, actual airchecking of talent is sadly becoming a less frequent management activity on the part of today’s programmers. You can probably attribute what seems like neglect to fact most PDs today wear several “hats,” making it more difficult to sit down with a personality for an hour to review a recent performance.

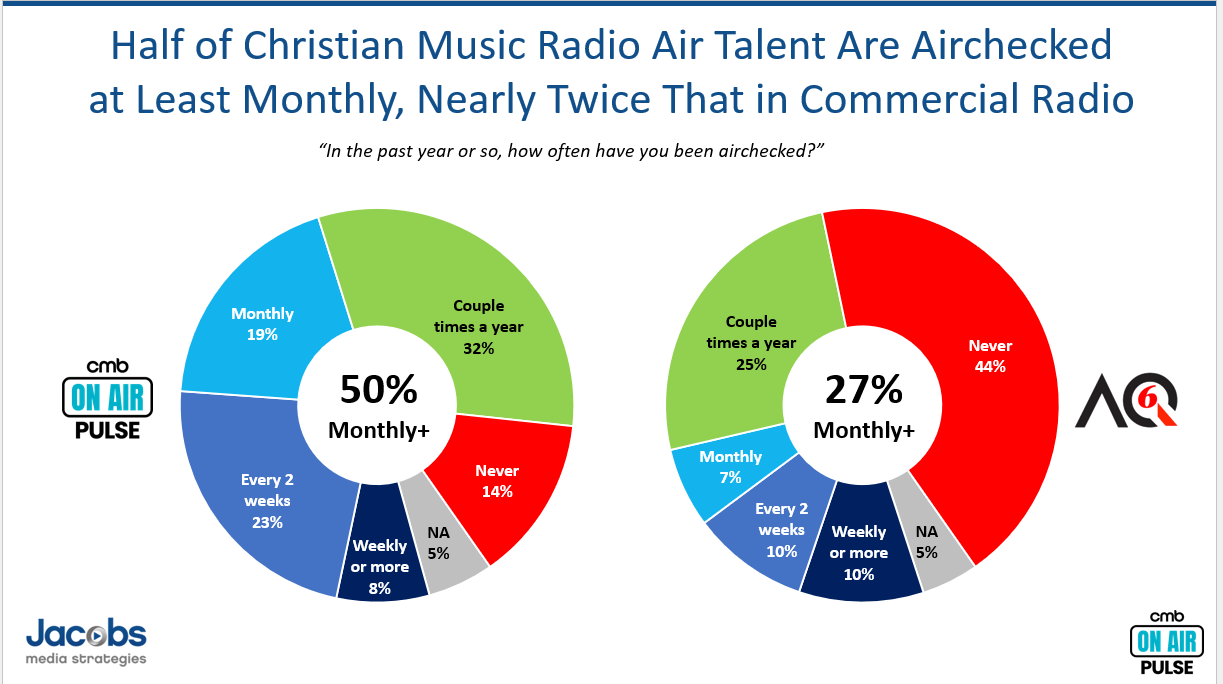

We have now asked the same question in our commercial radio research study of air talent (the AQ project) versus its equivalent in the Christian music stations. The differences are stark…and revealing:

In On Air Pulse, our Christian music radio survey of talent, only 14% say they’re never airchecked. Overall, half say their on-air work is reviewed at least monthly. Contrast that with our most recent investigation of commercial radio personalities—AQ6 from 2024. In that study—and it’s been consistent since we first conducted these studies back in 2018—nearly half (44%) tell us they’re never airchecked.

What effects has this degree of talent neglect taken on radio, particularly the thousands of commercial radio stations in the United States? And what is the root cause of these one-on-one evaluations being so less frequent nowadays?

To address the second question first, the fact so many P.D.s are wearing multiple hats would logically impact the amount of time they have available to work with their station’s talent. When you’re handling numerous tasks at the station, and in situations where programmers now oversee multiple stations often in different markets, you gain an understanding as to why airchecks have become rarities in so many operations.

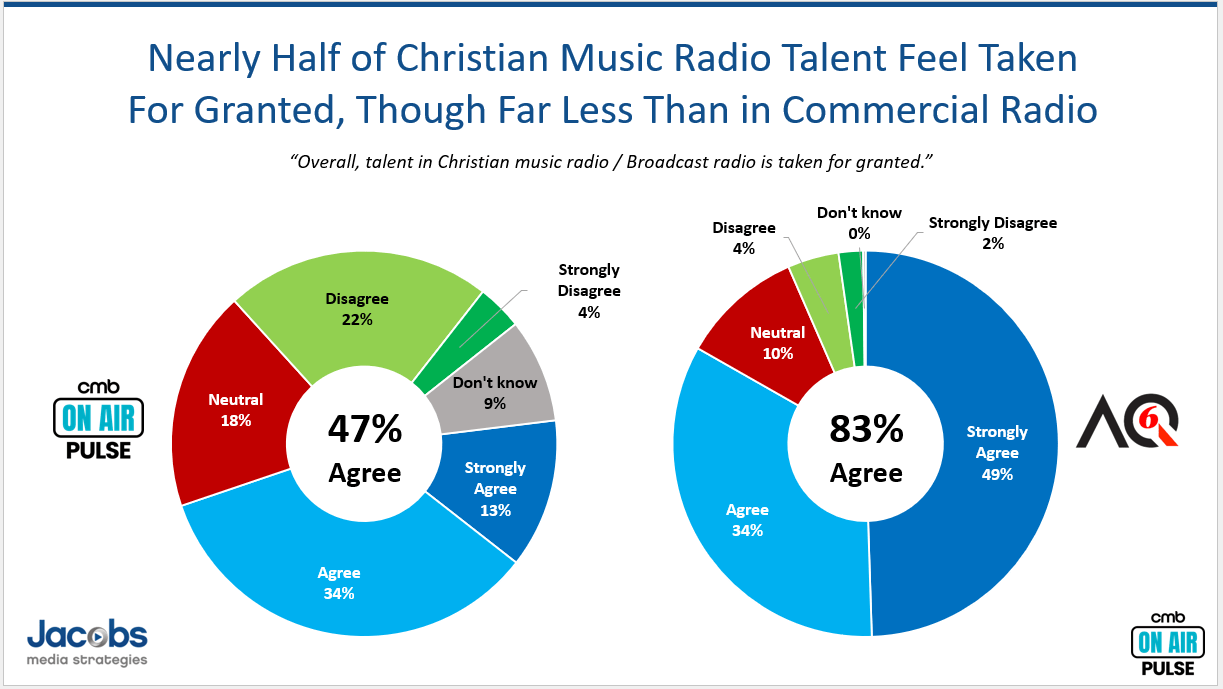

But the answer to the first question—determining the net effect of less airchecking—is more perplexing and potentially more brand erosive. As we’ve observed in our AQ studies, an overwhelming percentage of air talent give mediocre Net Promoter Scores—a recommendation measure—to both the stations and the companies they work for. And when more than eight in ten hosts in commercial radio (83%) say they feel taken for granted, connecting these dots indicates how neglect might sow a feeling of being ignored or worse—that sense one’s performance just doesn’t matter.

As more and more radio companies now see themselves as competing in the digital arena, the reality is that in order to compete with big, well-heeled tech and media organizations, the quality bar has been raised. The same old caliber of air talent and entertainment value is being pressure-tested every day against streaming, podcasts, satellite radio, YouTube channels, and the myriad of other competitive outlets vying for a consumer’s time and attention. A radio station that sounds “mailed in” or “paint-by-the-numbers” just won’t cut it in today’s marketplace.

Like so many skills and crafts, it often starts with the fundamentals—he foundation of the media offering itself. The Malcom Gladwell theory that it requires 10,000 hours to achieve expertise at a craft or endeavor has become a well-known yardstick. Translated to four-hour radio shows, that’s a total of 2,500 shows. For a full-timer doing five shows a week, it comes down to 500 weeks of radio—or about 10 years to become truly proficient at a skill like being on the air.

Now, some of you may dispute Gladwell’s requirement. And undoubtedly, his estimate of what it takes to achieve expertise in a discipline will vary by the individual and the task at hand. But how much sooner could many air personalities achieve greatness if he or she was receiving regular feedback, constructive criticism, and suggested improvement from a programmer who knows what they’re talking about?

In other words, airchecking. But if we’ve learned anything from broadcast radio’s journey over the past decade or two, is that attention to detail and being “brilliant at the basics” are lost arts—a part of the bygone history of radio like the cart machine and splicing blocks. And the onslaught of AI technology will only serve to lessen those tasks that now require time, judgement, and an ear for excellence.

This begs the question whether an AIrcheck where the bot is taught the criteria that constitutes a “good show” can ever replace the ear and the bedside manner of a great PD? And in the final analysis, is an AIrcheck better than what the 44% are getting now: nothing?

Ultimately, it comes down to those added “hats” that so many of those remaining in the radio workforce have had to take on. How does the lack of PDs with time, experience, and empathy impact radio’s place in the media universe, as well as its ability to serve advertisers and communities? We may never know the answers to these questions. But I think we do know—albeit subjectively—that all the scale broadcasters have achieved over the past 30 years has failed to produce better sounding, more profitable stations, as reflected by their performance and well as their value as properties.

Sometimes, it is something as fundamental as a basic activity that leads to the eventual degradation of a product, service, or organization. Like the basic aircheck, never one of the more fun tasks to-do, but clearly one of the most important investments in time, effort, and caring.

And remember, one thought per break.

In appreciation of his efforts, you might want to buy Jon Nelson “a cup of coffee” for recreating the Dr. Johnny Fever aircheck. I did. It’s $5 and you can access his page here.

Originally published by Jacobs Media