By Fred & Paul Jacobs

It’s strange, but when we think about the dire prospect of bankruptcy in radio, we’ve been conditioned to think about commercial radio. And why not? There have already been a number of these filings on the commercial side of the radio dial, not to mention the more recent rash of “turn-in-the-keys” incidents. And no one would be surprised if there aren’t more bankruptcies in commercial radio in the not-so-distant future.

But in public radio? Perish the thought. After all, these stations are government funded, seemingly impervious to the financial distresses commonly suffered by their commercial radio counterparts. But since COVID, that paradigm has shifted in public radio. Staff reductions are common, especially in the largest markets where staff counts easily run into the triple digits. As balance sheets have reddened, more and more public stations have had to prune employees, programs, and podcasts in efforts to get whole again.

And now, public radio has entered a new phase. The passage of President Trump’s “big but not so beautiful” recissions package has created a tectonic shift in public radio from WNYC to the most rural areas of Alaska. Every public radio station is feeling the pain of the unthinkable—seeing these federal dollars disappear. We hear the term, “existential crisis,” in every corner of business, political, and social discourse these days. But if you’re a manager of a public radio station or organization, this truly is one—that dreaded moment where we’re going to learn a great deal about management process, innovation, creativity, and cahones. Because the next year will require a mixture of all these attributes if public radio is to dig out of this hole, and emerge as a viable, relevant, and financially sound enterprise.

Don’t we know it. Fred has served on the board of the Public Radio Program Directors association, and has also helmed 17 Public Radio Techsurveys. And over the years, we’ve provided consulting and/or research for the likes of WAMU, KQED, KPCC (now LAist), WNYC, and scores of others, in addition to a decade with NPR, as well as project work for the BBC and its U.S. distributor, American Public Media.

consulting and/or research for the likes of WAMU, KQED, KPCC (now LAist), WNYC, and scores of others, in addition to a decade with NPR, as well as project work for the BBC and its U.S. distributor, American Public Media.

And Paul knows his way around public radio’s development and underwriting block as board chair of Greater Public, the organization that heads up these all-important functions at public radio—sponsorship and fundraising, of course, are the standout activities that keep public radio stations comfortably in the black and humming.

So, we see the dilemma and the opportunity from both sides of spectrum. And it is indeed a challenge. But it also broadly opens the doors of change, something that has been much-needed but rarely done in the past as most public radio stations have operated with much less financial pressures than their commercial cousins.

And believe it or not, there’s actually some good news here. As the New York Times reported the other day, listeners are more open than ever to opening up their wallets and purse strings due to the Congress’ vote to end CPB funding starting this fall.

In “Donations to NPR and PBS Stations Surge After Funding Cuts,” Benjamin Mullin tells us the money is pouring in—a fact we can corroborate in discussions with public stations with whom we work. In fact, many listeners didn’t wait for the financial “claw back” by Congress to pass last month—they’ve been donating heavily since Trump’s 2.0 tour began.

Oddly, it’s almost as if many fans of Morning Edition, and Wait, Wait…Don’t Tell Me! were anticipating these draconian moves, getting out in front with their donations. Mullins reports new contributors are stepping up as well, an especially encouraging sign.

But as Mullin reports, it’s likely not going to be enough to offset the government dollars shortfall. This is especially true in small markets where federal funds make up a much larger share of operating budgets and there is a smaller population to ask for support from.

So, what is public radio (we cannot speak for the television side) doing to ensure its survival and sustainability? Sadly, not enough.

The prevailing attitude is the familiar “wait & see” approach to determine just how robust donations will be in this new era for public radio.

And the fundraising mechanism of choice is (….wait for it…) those tired & true pledge drives. And while they still bring home the financial bacon, they are terribly unpopular, even among those who succumb to their pleas year in and year out.

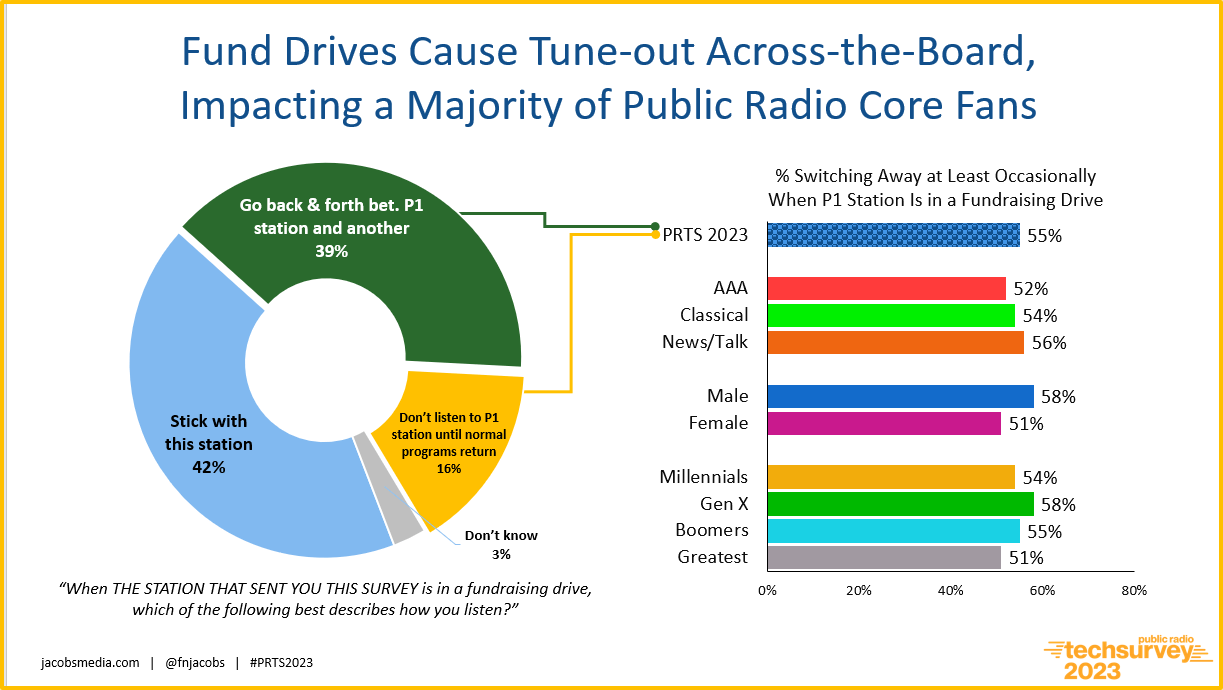

As we have learned all too well in our Public Radio Techsurveys, they are most certainly listening turn-offs, driving down ratings. It is always easy to see which weeks stations were “in pledge” when you get a look at the ratings weeklies. The data slide below illustrates listener blowback, as even many donors turn stations off while they’re in an active pledge cycle.

One area where public radio has made definitive gains is with so-called “sustainers”—those who opt to make a monthly ongoing donation, rather than only giving once or twice a year. The regularity of what’s known as “sustaining membership” has become an important arrow in public radio’s financial quiver.

But the problem is that “sustainers” tend to be even more disdainful of pledge. After all, they’re already giving—every month. So, why must they endure a week (or more) of mind-numbing pledge drives interrupting their favorite public radio programs?

And yet, there’s often a palpable fear of attempting new, different, and possibly breakthrough fundraising strategies. Rather than having a number of ongoing donation events and mechanisms, most public radio stations continue going to the familiar, but tired “pledge well.”

Public radio vets have seen this movie before—notably, the “Trump Bump” that took place during the first administration. It was short-lived, followed by the notorious “Trump Slump.” Savvy forecasters would be smart to assume the current donor surge will not be sustainable, especially if pledge continues to be the default fundraising tool.

There’s evidence to suggest that public radio could benefit from new and different strategies and tactics. Our work with Children’s Miracle Network, the organization that raises hundreds of millions of dollars for local children’s hospitals, features many innovative fundraising events. Beyond “radiothons” with local stations, CMN also has developed dance marathons, golf tournaments, round-up with retail partners, and even a gaming platform. Bottom line? You’ve got to connect with a broad range of donors if you wish to develop a system that can go the distance.

Speaking of which, this Thursday (7/31) is “Miracle Treat Day,” a CMN collaboration with Dairy Queen formed decades ago. At least $1 from every Blizzard sold that day goes right to local Children’s Miracle Network hospitals.

Children’s Miracle Network hospitals.

As more proof that Fred walks the walk, note the photo of him demonstrating the anti-gravitational effect of DQ’s Blizzards. More info on this year’s “Miracle Treat Day” here.

The political spectrum is another case in point, abusing the “text-to-donate” model with each passing day. But some candidates are breaking away from monolithic fundraising models, as ways to not only raise money but to reach voters who are numbed by the “same old same old” techniques.

Here in Michigan, State Senator Mallory McMorrow is running a series of “brewery tours” across the state, more casual ways to connect with constituents—and of course, to garner donations. And the demographics at these events almost always skew younger.

Axios reporter in Detroit, Joe Guillen, tells the story about this strategy in “McMorrow’s beer tour aims to reach new voters.” It turns out McMorrow worked as a bartender while in college, so she’s no stranger to these venues.

And as an added bonus, McMorrow says these events serve as an informal audience research tool, helping her to get a better sense of the public:

“I love how creative the industry is. … Just popping into a brewery gives you a really good taste of the locals, and it’s where they hang out.”

Obviously, McMorrow isn’t taking fundraising as seriously as most veteran incumbents. No, that doesn’t mean she’s not about donors, but she realizes there are innovative alternates to those awful “rubber chicken” dinners and conventional donor events.

And that’s why Buffalo Toronto Public Media’s latest splash caught our attention. Tom Calderone, who runs the place, recently took to TikTok to drum up some attention to this public media cluster, making an important “celebrity ask.”

@btpublicmedia @colbertlateshow, we need to talk ‼️🚨 We know you’ve had a rough week… so have we. But together? We’d be unstoppable. Call us, Stephen. We have ideas.😉📞 716-845-7001 #stephencolbert #publicmedia #pbs #cbs #lateshow #trending #fyp ♬ original sound – Buffalo Toronto Public Media

It’s called “thinking big” and it’s a mindset that’s been all too rare in public radio circles over the years. We were reminded of this during the 40th anniversary of the amazing, historic “Live Aid” concerts that took place both in London and Philadelphia with the audacious goal to “Feed the World.”

Interestingly the vision of “Live Aid” was the the brainchild of Boomtown Rats founder, Bob Geldof. His band’s only major hit, the iconic “I Don’t Like Mondays,” was a far cry from bigger groups from his era. But it was Geldof’s dream to raise money to feel starving Africans, specifically Ethiopia.

On that note, Fred was contacted last week by the glib Danny Buch (pictured), long time music supporter, rep, and promoter. His question addressed to many radio programmers he contacted:

How can the artist and music community help non-comm radio through this crisis?

through this crisis?

Fred’s response? A large-scale concert, along the lines of a “Live Aid” or a series of smaller ones (like “Bake Sales”) that could tour from market to market.

Danny is culling together numerous responses from the radio community. But it will take a major effort on a big scale to help smaller non-comm and independent stations stay afloat during this unprecedented test of public radio’s finances and its will.

There’s no question a hot topic at the Public Media Content Collective conference in August will be fundraising. For public radio, emerging from this squeeze in good—if not better—shape will require innovation and creativity, to be sure. It will also require open mindedness and even a mindset of not taking everything so seriously.

Seriously.

And if Stephen Colbert decides to make that trek to Buffalo this year, you’ll be the first to know.

Originally published by Jacobs Media