With all the other exciting news swirling around these days, you may have missed the item that a certain lead singer of “the greatest rock n’ roll band in the world” just celebrated his 82nd birthday. That’s right—that milestone belonged to Mick Jagger and his Stones—still touring even though the main players are octogenarians.

Of course, Jagger and Richards warned us about the perils of the aging process. In their hit, “Mother’s Little Helper” from 1966, they warn about the ravages of getting old from a mother’s point of view. Ironically, the song is so old, even most Classic Rock stations don’t play it anymore. In radio format parlance, it has “aged out.”

All of this is part of a larger issue. So many signs point to so many things getting “long in the tooth” (like that hackneyed phrase). That’s certainly the case for radio, an industry that has gotten old right before our very eyes. Based on the last few administrations, our presidents are old, and most of the movies coming out are part of older franchises or are reboots of a vintage flick.

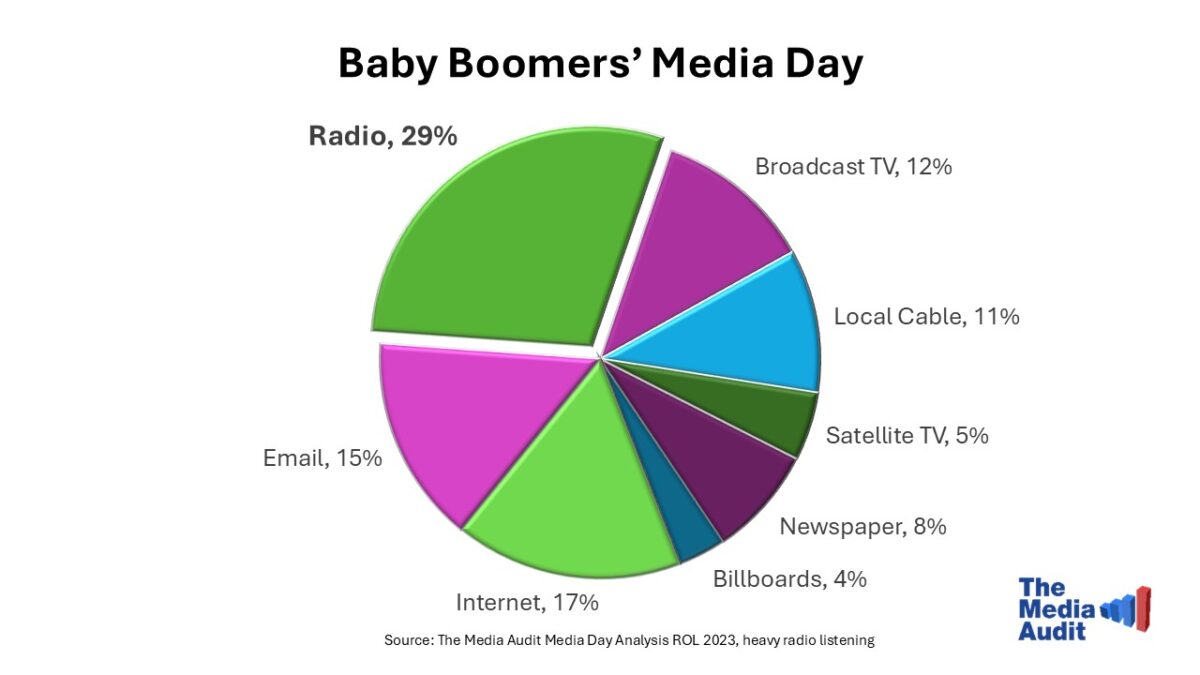

Recently, the RAB tried to convince us the 55+ audience matters. The article in question, “Engaging with Consumers Who Have the Cash to Splash,” was written by the RAB’s SVP/Insights Annette Malave.

Annette made all the key points—that Baby Boomers are the wealthiest generation with cash to spend. Whether we’re talking about new homes and new cars, it’s those aging Boomers most likely to form brand loyalties and actually buy these big ticket items.

And it shouldn’t escape radio people that these consumers are the most frequent listeners to broadcast radio according to The Media Audit:

via RAB

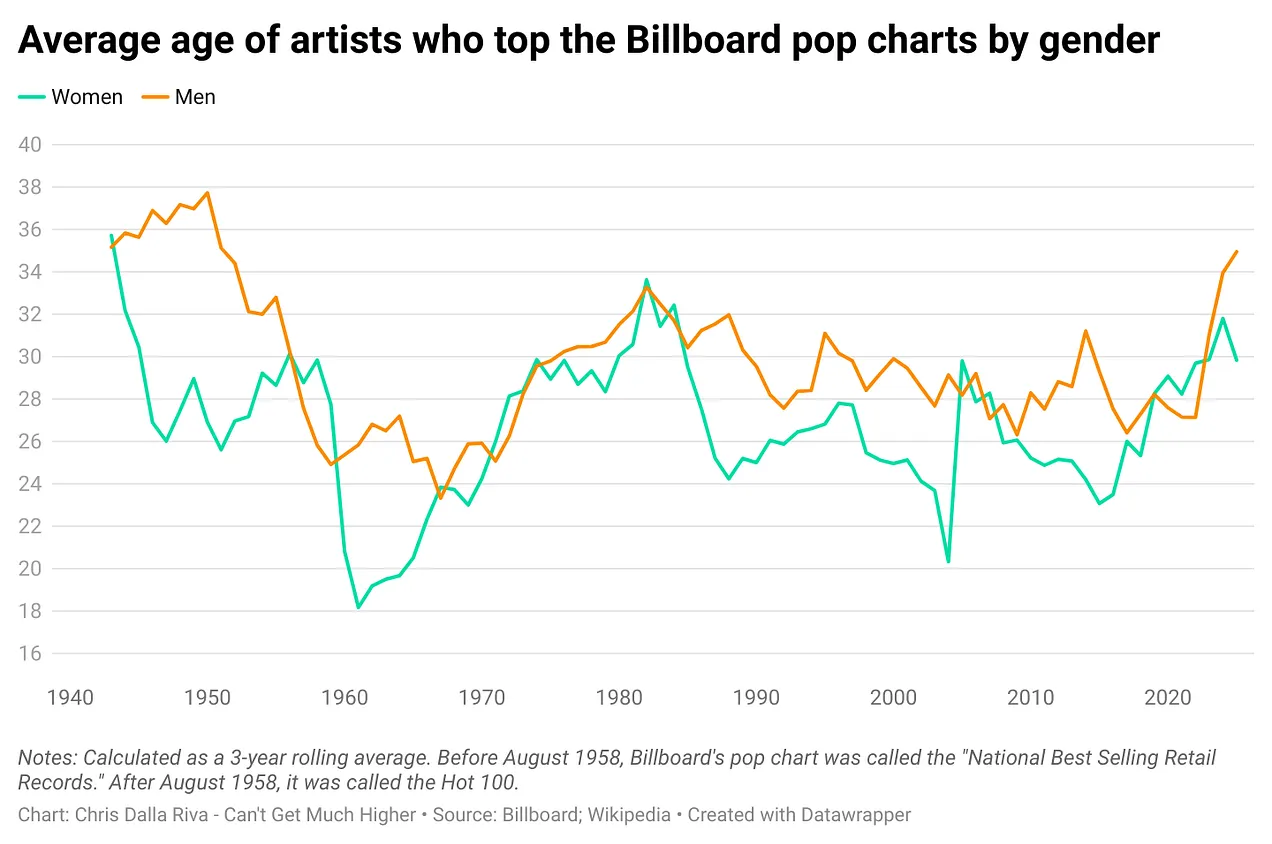

So when Mike Stern sent me “The Return of the ‘Elderly’ Pop Star” by Chris Dalla Riva last month, the analysis grabbed my attention. He takes a similar approach to “data storytelling” as Daniel Parris’ “Stat Significant,” who I’ve highlighted a number of times in this blog.

Unlike Daniel, Dalla Riva is a musician, so his perspective on this exploration into what he calls the “pop music gerontocracy” is especially insightful. He mentions that his research took him down a musical rabbit hole where he listened to every song to ever top the Billboard Hot 100. In the process, he took notes and gathered additional information about every one of these songs.

And one of those data pieces is the age of the artists themselves. In the World War II period, Dalla Riva points out most pop stars were in their mid-30s. But by the Kennedy Administration, the average age of a pop hitmaker started dropping significantly. And he attributes much of this phenomenon to the preponderance of Baby Boomer teens driving music trends during the ’60s.

By the ’70s and into the beginnings of the MTV Era, the age of the average pop icon jumped from 24 all the way up to age 32.

The ’90s ushered in another youth movement, as the average pop stars of that era had fallen back to the 26-28 year-old zone.

And that brings us to where we are today. Over the last five years, pop stars are indeed aging again, moving into the 33 year-old zone.

Note the gold line—male artists. They tend to be older than female artists (aqua line).

While Dalla Riva isn’t especially concerned about aging hitmakers, he does remind the labels of the need to make investments in new artists and groups rather than stocking up on Pink Floyd’s or Queen’s catalogs.

In his analysis, Dalla Riva also points out that for many of the most legendary artists, they had done their best work while still in their youth. I can’t help but think that for many of us, our most creative years—at least potentially—was when we were in our twenties. Think the Beatles, the Stones, Steve Wonder, and so many others. He also brings up Billie Eilish whose initial impact was made when she was still a teen.

It’s not that most of the music Paul McCartney or Garth Brooks have released in recent years is of poor quality. But their recent music pales in comparison with the songs they wrote and recorded when they were young performers in their twenties.

when they were young performers in their twenties.

We may be loyal to an artist—enough to fork over money for pricey tickets along with expensive merch when they come to town. But when they break out a new song in concert, it has become very common to watch throngs of people head to the concession stands or the restrooms to wait out this time devoted to a newer song. They come for the time-tested big hits.

The same may be very likely the case in radio, too. Most of us were at our most creative, motivated, and energized when we were in our twenties. As we age, it is human nature to become less enamored with risk and more measured when we’re in our thirties, forties, and beyond. It’s human nature.

All this is yet another reason why radio companies should more aggressively put twentysomethings in charge of their brands moving forward. While it won’t work across the board, it has more of a chance to succeed than most people think.

Too many of us Boomers (and yes, even Xers) may have stayed too long at the “radio dance.” Now, it’s time to hand over the reins to someone leaner, meaner, and hopefully, more incisive and more focused on new media opportunities.

If radio is to reverse or even slow down its march to the media congregate living facility, it will need to shift its emphasis to younger programmers and more youthful target audiences. And maybe the record labels will start making a more concerted effort to discover and build younger, more passionate performers.

The Irish playwright and author, George Bernard Shaw, reminded us about the wastefulness of being young:

Originally published by Jacobs Media